How does China control the wealth of developing countries through its "generous" loans?

New evidence shows that China allocates at least twice as much development money as the United States and other major powers to poor and developing countries, much of it in the form of risky high-interest loans from Chinese state banks.

The sheer amount of Chinese lending is astonishing. Not so long ago, China was receiving foreign aid, but now things have turned.

Over the course of 18 years, China has awarded or loaned money to 13,427 infrastructure projects worth $843 billion in 165 countries, according to the AidData Research Center at William & Mary University in Virginia.

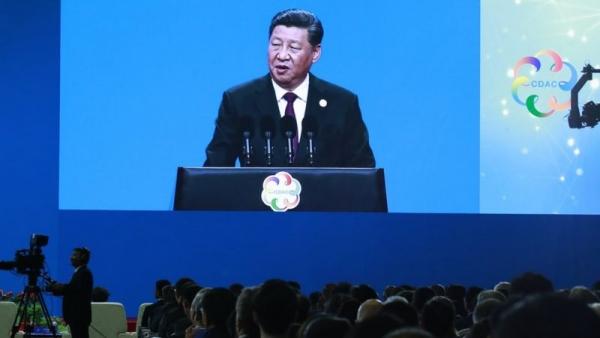

A large part of this money is related to the ambitious "Belt and Road" initiative of Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Since the launch of this initiative in 2013, China's expertise in infrastructure projects, and the availability of foreign currency, has been leveraged to build new global trade routes.

Skip topics that may interest you and continue reading topics that may interest youTopics that may interest you at the end

However, critics fear that the high-interest loans that fund many Chinese projects are burdening borrowing nations with high debt.

Chinese officials seem unaware. AidData researchers, who have spent four years tracking all global lending and spending in China, say Chinese government ministries turn to them regularly for information about how Chinese money is used abroad.

“We always hear from government officials in China that they can't get this data internally, but exclusively through us,” explains Brad Park, CEO of AidData.

A zigzag railway line running between China and neighboring Laos is often a prime example of unofficial Chinese lending.

For decades, politicians have thought about this connection, linking landlocked southwest China directly with Southeast Asia.

But experts and engineers have warned that the cost will be prohibitive, as the tracks will need to pass through steep mountains, requiring dozens of bridges and tunnels. Laos is also one of the poorest countries in the region and cannot afford even a fraction of the cost.

Here, a number of ambitious Chinese bankers appeared on the scene, and with the support of a group of Chinese state companies and a consortium of Chinese government lenders, the project is starting to see the light, and the railway, which will cost 5.9 billion dollars, is scheduled to start work next December.

But Laos had to take out a $480 million loan from a Chinese bank to finance the small part of its stake in the project. One of the few sources of profit in Laos, the proceeds from the mines of potash (salts containing potassium), was used to guarantee the huge loan.

Skip the podcast and keep reading My Teen Podcast (Morahakaty)Teenage taboos, presented by Karima Kouh and prepared by Mais Baqy.

Episodes

podcast end

“The loan that China’s Eximbank provided to cover part of the capital really shows how determined the Chinese state is to go ahead with the project,” explains Wanning Kelly Chen, associate professor at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Most of the line is owned by a Chinese-dominated railway group, but under the vague terms of the deal, the Laos government is ultimately responsible for the railway debt.

The lopsided deal has led international creditors to downgrade Laos' credit rating to a "very bad" rating.

In September 2020, Laos was on the brink of bankruptcy, sold a major asset to China, and handed over part of its power grid for $600 million in order to obtain debt forgiveness for Chinese creditors, all before the railways began operating.

The Laos railway is far from the only risky project funded by Chinese state banks, and AidData says China remains the number one financier for many low- and middle-income countries.

“On average, China's international development financing commitments are about $85 billion," says Brad Parks. "By comparison, the United States spends about $37 billion a year to support global development activities."

AidData says that China has vastly outperformed all other countries in financing development, but that the way Beijing has reached this level is "extraordinary".

In the past, Western countries were responsible for implicating African countries in particular in high-interest debt. But China lends differently: Instead of financing projects by granting or lending money from one country to another, almost all of the money it provides is in the form of government bank loans.

Such loans do not appear in the official accounts of government debt, because central government institutions are not mentioned in many of the deals concluded by Chinese state banks, which makes such deals outside the government’s balance sheets, and obscured by confidentiality clauses that can prevent governments from knowing what It was agreed behind closed doors.

AidData has recorded debts about which not enough details are known, amounting to $385 billion.

Many Chinese government development loans also require unusual forms of collateral. Chinese loans appear to require borrowers to pledge to repay in hard currency cash from money generated from the sale of natural resources.

The deal with Venezuela, for example, requires a Venezuelan borrower to deposit foreign currency from the sale of oil directly into a Chinese-controlled bank account. In the event that the debt is not paid, the Chinese lender can withdraw the cash placed in the account immediately.

Brad Parks explains: “It really sounds like a kind of strategy they use to assure the borrower that they have the upper hand. Their message is, 'You're going to pay us before anyone else, because we're the only ones in control of this precious wealth.'"

Is China smart? asks Anna Gilburn, a law professor at Georgetown University who co-authored the AidData study earlier this year scrutinizing Chinese development loan contracts.

“I think our conclusion is that these contracts have revealed their strength and sophistication,” Gilburn says. “They are very much protective of their interests.”

Gilburn also explains that countries can be difficult debtors, as it is not practical to expect them to hand over a physical asset, such as a port, if they are unable to pay their debts.

China may soon face some international competition in lending. At a G7 meeting last June, the US and its allies announced that the G7 was adopting a spending plan to rival China's influence, which promises to finance financially and environmentally sustainable global infrastructure projects.

But this seemingly ambitious plan may have come too late.

“I doubt that Western initiatives will significantly affect the Chinese program," says David Dollar, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former US Treasury representative in China.

"Those new initiatives will not have enough real money to meet the scale of infrastructure needs in the developing world. Working with Western official funders is bureaucratic and subject to long delays," he adds.

AidData researchers have found that the "Belt and Road" initiative faces its own problems, as it appears that this initiative is more likely to be suspected of corruption, scandals in employment conditions, and environmental issues, compared to other Chinese development deals.

Researchers say that to keep the Belt and Road Initiative on track, Beijing will have no choice but to respond to borrowers' concerns.